By Rick Lewis

Coming out of sedation after six days on a ventilator, my mother saw a demon. A horned, ugly thing, it sneered at her as she struggled to open her eyes and rid herself of it. In her weakness, and under the lingering influence of a potent cocktail of sedatives and pain relievers, all she could do was repeat to herself again and again: “I am marked as Christ’s own forever. You cannot touch me. I am marked as Christ’s own forever.”

~~~

The COVID-19 virus is, put simply, a beast. It has shown itself to operate in unpredictable ways from patient to patient—lightly touching some while others it takes to the mat with swift ferocity. We have all witnessed the withering trail of physical devastation it has wrought throughout the country, essentially carving absence into communities of previous abundance (as of writing in late July, the U.S. death toll stands at just over 150,000). But, perhaps most troubling, it remains incompletely understood. And, trust me, uncertainty tries the mind in uniquely twisted ways. I should know. In June, everyone in my immediate family, excluding my father, contracted the virus.

I will be the first to say that we did what we could to protect ourselves: staying home as much as possible, wearing masks while out, obsessively washing our hands and so on. However, you are only as strong as your weakest link, and when others fail to be as vigilant…well, snap.

~~~

It was on Thursday, June 18 that my mom, Rufie Lewis, first came down with a fever, two days after her 60th birthday. For several days, there was only miserable sickness for her: all-day fevers, chills, nausea and debilitating fatigue. I remember her calling out for help one day and entering her room to see her shaking so violently from a fever I thought she may have been having a stroke.

That Sunday, we took her to the ER. A chest X-ray showed a small spot of pneumonia in her left lung, and a rapid COVID test came back positive. She was sent home with a Z-Pak and told to monitor her symptoms.

On Wednesday of that week, at the recommendation of a doctor in the family and after no improvement of her symptoms, I drove her to UAB’s COVID Respiratory Clinic, a downtown operation run out of the shell of a deceased bank. When they took her in on a wheelchair, I had no idea I wouldn’t see her again until the Fourth of July.

~~~

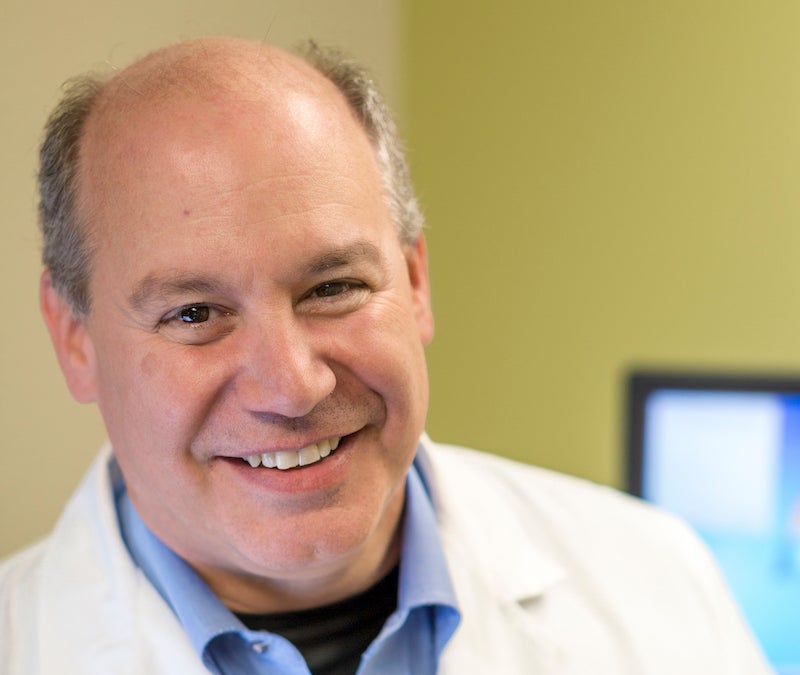

Dr. Michael Saag

When I dropped mom off at the clinic, one of the nurses told her that she was in good hands and that one of the doctors at UAB had gone through a bout with the disease himself. It was both difficult and reassuring to hear that one of the physicians might know enough firsthand to bring some clarity to the ever-evolving menace behind mom’s struggle as well as that of many others.

Dr. Michael Saag, M.D. is no stranger to uncertainty. He has dedicated much of his career at UAB to the research of infectious diseases; in particular, he has worked extensively on AIDS/HIV research and saw what it was like for a new disease to create a similar matrix of fear, hesitation and destruction like COVID-19. But that didn’t mean he was mentally prepared to get this coronavirus himself.

After a road trip in early March, coming back from New York City with his son, Saag and his son (who is also a physician) began to feel unwell—fevers, chills and body aches. They self-quarantined in their rooms when they got home to Mountain Brook and stayed aware of their symptoms. His son’s case was mild and went away in a few days, and until the sixth day, the same seemed to be true for Saag: “I thought, well this is over. And then that night was the beginning of what I call the Twilight Zone meets Groundhog’s Day.”

The “Twilight Zone” would start at night, around six in the evening, and his symptoms, including a new mental haziness and shortness of breath, would “crescendo” until midnight or 2 a.m. He would experience an “eerie feeling … of impending doom” that lingered in his thoughts, not knowing whether or not he’d make it through the night without needing to go to the hospital.

“The next morning, I would feel pretty good and say, ‘Okay, maybe that was it,’” he says. “And then, sure enough, the next night, it would all return… So the Twilight Zone was that feeling of unknown, not knowing what was gonna happen next. And Groundhog Day went on every day for eight days in a row.”

Finally, after nine or so days of having the virus, Saag’s condition seemed to improve. But it took several weeks for him to feel “right.” The physical effects of the virus are not to be trifled with for many Americans, especially those that are older or have pre-existing health conditions, but the mental anguish of the disease can be just as potent.

“It’s a scary experience mostly because it’s an unknown. It’s unknown what’s going to happen next,” Saag explains. “For me as a physician, I knew what I was facing if I ended up in the hospital. It was not just some amorphous, ‘I’ve got to go to the hospital, and I don’t know what’s going to happen there.’ If I went to the hospital, I knew precisely what was going to happen.”

Namely, being put on oxygen, or worse, a ventilator. With a ventilator, there would be a total loss of control, usually sedation, and the knowledge that perhaps weeks of your life would be willed away to the siphon of medically induced memory loss.

~~~

When my mom was taken into UAB’s COVID Respiratory Clinic on her sixth day with the virus, the clinic took a new chest X-ray. In just four days’ time, her earlier “spot” of pneumonia had progressed to advanced pneumonia in both of her lungs. A nurse came outside and told me through the car window that she was put on oxygen and would need to be admitted to the hospital immediately, that hopefully a bed would be open in the COVID ward that evening. Of course, as was and is operating procedure, no family would be allowed in with her or allowed to visit her.

About an hour later, in a tellingly grim call, a doctor would inform me that the ward was currently full and that Mom would have to stay in the ER until a bed opened up. I would receive another call that night from mom as she sat in the ER waiting room: “Rick, I’m going to die here,” she said.

~~~

Banks Henderson

A key aspect of this coronavirus, and arguably one of the main reasons for its continued community spread, is its unique interaction with each individual who contracts it. More explicitly, many people won’t ever get symptoms, and many others may only get the mildest of symptoms.

Banks Henderson, a 2017 Mountain Brook High School graduate, is now a 21-year-old student at Auburn University and a youth minister at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Auburn as well. Toward the middle of March, he returned from Florida from a spring break trip with friends.

“About a week and a half after that, I just started feeling tired, not really up to do anything,” he explains. “I remember sitting there, and my family was having drinks out on the back porch, and they’re like, ‘You wanna have a drink?’ And I said, ‘No, I’m gonna actually go lay down.’”

When he took his temperature, he had developed a fever. The fever would come up and down throughout the day, as would the fatigue. This continued on for about a week before Henderson noticed a little difficulty breathing: “It wasn’t bad. I would just get out of breath while walking up the stairs.”

After that, he went in to get tested and got a positive result for COVID. But almost as soon as he’d seen a doctor, the symptoms essentially disappeared.

“The next day after I went to the doctor, I was symptom-free,” he says. “So it did not last long for me whatsoever. It was about maybe a week and a half of feeling cruddy. I had the flu last year and felt 1,000 times worse with that than I did with Corona.”

And, frankly, the same was true for me. While helping to take care of my mom at home before she was admitted to the hospital, I also contracted the disease. It amounted to a night of intense chills and a low-grade fever and body aches for about three or four more days. A test on the fifth day proved I had it. All of those days I spent cloistered away in my room, as well as the following two weeks for good measure.

Because, while I (and my brother, for that matter) was blessed with a mild case, my dad, Charles, who also lives in the house, was a prime target for a serious reaction. Miraculously, he has thus far avoided it. However, I can say that the weeks that I was either sick or still contagious were not easy ones. The spectre of COVID was always present on my mind, and I was fearful to even momentarily exhale when I was near my doorway. It was like living in a house filled with haints I could not afford to disturb.

~~~

Anyone who knows or has met my mom can attest to her ability to captivate anyone with her smile or unabashed laughter. She radiates sunlight from her very pores and has the personal spirit to boot. That’s what makes the idea of her very being alienated by tubing and IV drips so difficult to imagine, especially with the speed at which she declined. It was not unlike watching a video of a building demolition: there’s a loud explosion and, many times, a pause before the structure fully buckles onto itself.

One moment a COVID patient can be doing okay—Mom was on a simple oxygen tube for about three days—before they take a meteoric dive or make a stunning recovery. On her fourth or so day at UAB, she was told she was being taken to the ICU to be put on a ventilator for her worsening oxygen saturation, and she only had time to make a quick call to Dad before being put under.

For her, the rest is a grey wash of fluorescent light, the ever-present white noise of hospital sound, and the memory of the nurses’ motivation board across from her glass-boxed room: “Be Strong, Be Happy.”

What she does not remember is the video call we had with her, the almost hourly phone conversations we had with the nurses to get updates on her condition, or the faces of the patients around her. The swoosh, click, push, swoosh, click, push of her external lungs.

~~~

In the end though, Mom came home to our perch in Brookwood Forest. After roughly two weeks in the hospital, Dad drove her into the driveway on the afternoon of Independence Day. It was likely the combination of dexamethasone, remdesivir, prone therapy, and amazing nurses and doctors who helped her recover in such a short period of time compared to many of the earlier cases in the pandemic.

When I asked her how the knowledge of her near-death has modified her ability to get bogged down in the worries of each day, she explained that she is “just so thankful to be alive. I don’t want to focus on negativity or little things that could distract me from what I have to live for, my faith and my family.”

My mom is a deeply religious person and finds both comfort and solace in times of prayer and reflection. And so, whether or not the “demon” she faced in the hospital was a shockingly common COVID-hallucination or a spiritual manifestation of her struggle, I have to imagine that her will to persevere and be whole again had a lot to do with where she is now: home and on the mend.

But the experience also made her more aware of the fragility of our time here and the potency of this disease: “It’s real,” she says. “It’s real.”