By Rick Lewis

Photos Contributed

Before the many metamorphoses of Crestline that would come in rapid succession through the late 19th century and over the course of the 20th, there was forest. Thick oaks and pines communed with birdsong and deer. American Indians of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee or Creek tribes traversed the spinal ridge along the high side of Euclid Avenue and the well-trodden trails where Montevallo Road now lies. Streams and creeks ran wild and untamed through Shades Valley, carving their serpentine tracks into the landscape.

It is almost too easy to separate this image of untouched Crestline from the beehive of activity that it is today, especially considering that this transformation seemed to happen overnight. Once the fledgling industrial-escape community was founded on the southern slope of Red Mountain, it took off like a sapling in fertile soil, but for many people that still remember the early days of Crestline, or “Club Village,” there exists a certain charm to what it was before, to its period of lankiness and knobby knees, still deciding what it would be when it got older.

Here we share the stories of Crestline residents both older and younger, to capture some images and musings of what Crestline looked like and felt like, and also how it grew over the course of the last century. Of course, it will be imperfect in telling anything approaching a robust history of this place, but is it not fun to reminisce?

Chapter I: The Cows of Club Village

At 88, Joan McCullough Scott can intimately recall a Crestline of time past that many of us are unfamiliar with. “We were newcomers in 1915,” she says. “There were many, many unpainted, waterless, electricity-less cabins all over the area…[people] just sort of lived off the land.” In the early days of Crestline, referred to for a time as Club Village after the construction of Birmingham Club, many of these cabin-residents were of a hardier ilk. Case in point, sometimes on walks with her father, they would come across stills operating in the woods: “My father would say, ‘Do not touch anything. Don’t bother anything, and we’re gonna move on fast!’”

Indeed, today’s spacious homes on postage-stamp lots and bustling commercial strip belie what was largely pastoral farmland, peppered with swaths of old growth forest, when Joan’s family moved to a farmhouse on a 50-acre plot of land off Montevallo Road. And while Joan, the youngest of seven, wouldn’t be born until 1932, for a period, the area stayed relatively stuck in time.

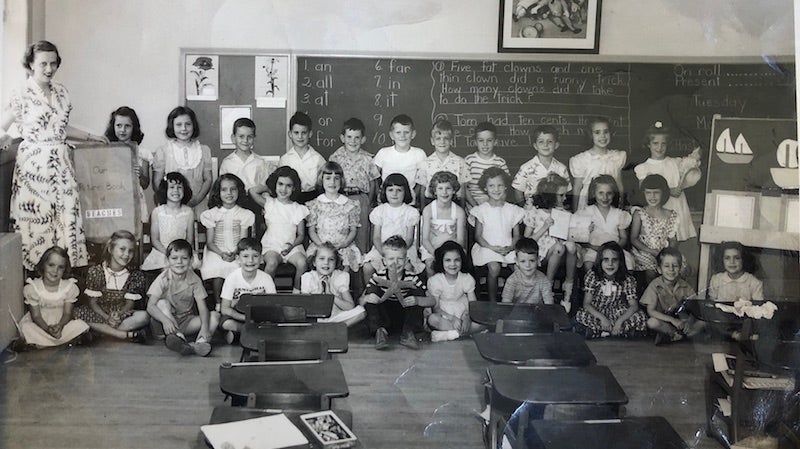

As a little girl, Joan remembers briefly attending what was then known as Crestline Heights Elementary School, “a two-story wooden building” for grades first through eighth. A county school at the time, Joan remarks that they “hardly ever got through the whole year without the taxes running out,” the children being let loose on parents as early as April. But an even more alien idea might be that of Crestline as a milk-producing powerhouse.

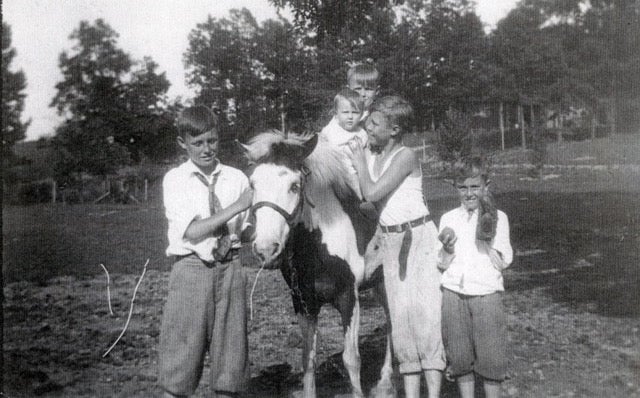

“When my parents moved in, there were five dairies in the area. One was now the Birmingham Country Club golf course,” Joan explains. During the Great Depression, one of the dairies, White’s, even distributed free pails of milk to families in need. As for the McCulloughs, they kept their own cows, horses (including a pony, Laddie, that she would ride in and around town), pigs and chickens on their land. “We had milk cows. I’d have to go … every morning and get the milk, which made my car very, very ‘fragrant,’” Joan recalls. “We kept [the milk] in the family. We had a blue pitcher, and when all of us were home, they would fill the pitcher with milk, and we could have all the milk we wanted.”

Chapter II: The Post-War Boom

It was mainly after World War II, with its influx of young, returning soldiers looking to stake a spot for themselves and their new families that Crestline and its surrounding areas would see a blossoming of buildings. Seemingly overnight, forested land was cleared, creeks were tamed, and little bungalow homes popped up like so many dandelions. The quaint, over-the-mountain community was seen as both affordable and clean—separated by a literal wall of trees and rock from the pollution of the city and its smoking foundries.

It was also around this time that Crestline would lean into a modernization of its infrastructure. Kaydee Erdreich-Bremen’s family moved into the area in the 1940s, and she remembers when many of the streets seemed like throwbacks to another era. “The Tot Lot alley was not paved, and the street across from the Crestline playground was not paved,” she says. “There were certain streets that were just still dirt roads.” Even Montevallo Road, busy by-way that it is now, wasn’t asphalt covered until after the war, shaping the way for more development.

Kids like Kaydee played in the streams and fields, explored the hills for arrowheads, and took pocketsful of change down to the five and dime store. But perhaps one of the more striking observations during this time of settling in and establishment is that everyone was seemingly common or at least on similar playing fields. “Nobody had a washer-dryer…We all wore the same saddle oxfords or brown lace-up shoes,” Kaydee says. “I laughed that I had no idea whose family had money and whose family didn’t. We were all in the same boat.” There were presidents of industry and firefighters on the same block, and they were all there for what Kaydee’s father described as “an area that never lost its value” with all of the conveniences of a small town close at hand: a grocery store, pharmacy, library and post office all within a short walk of each other.

Chapter III: Lingering Woods

Chapter III: Lingering Woods

Lanier Isom, 55, is intimately familiar with what it means to inhabit a piece of history. As the daughter of Joan McCullough Scott (featured above), she lived in the home of her grandparents and parents throughout her childhood, only to purchase the home from her mother and live there as an adult with her family. They finally sold the home in 2017, at which point it had been in the family for just about 100 years. The sense of history attached to the place was at once immutable and yet different. Just like the sense of the larger community around it, it had changed and yet, in many ways, was the same.

Lanier grew up with the Crestline of the ’70s and ’80s, a more in-focus vision of the village in terms of today’s lens. However, the quintessential memories she has of her childhood ring differently, filled with an element of nostalgia for days gone past: “We roamed the neighborhood. We rode our bikes for hours. We didn’t come home ‘til dark. We played kickball. We rode big wheels. We had pinecone battles. We built forts. We played badminton. We were outside all the time.”

It’s a litany of things not unfamiliar to the kids of current Crestline, but, in Lanier’s telling, there’s a natural element of lingering woods, a sense of unadulterated freedom free from technology and modern worries, and the intoxicating spirit of the last mysteries of an almost-fully-developed neighborhood still left to discover that might not be entirety replicable today.

For all of the change that Crestline has undergone over the decades: the carving and pavement of roads, the felling of timberland, the ushering in and out of cows, the explosive expansion of post-war construction, the changing of businesses and filling out of the town’s space; there still lives a very palpable sense of constancy there, a feeling of familial intimacy, of closeness and a sense that things can remain the same no matter who comes and goes.

Gas Town

If you speak with anyone that grew up in Crestline in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, you’ll hear

common reminiscing of the stores of old. There was Ariail’s drugstore with the soda fountain, Taylor’s store for everyday goods and a choice candy selection, and the A&P grocery. But talk long enough, and you’ll also hear an almost inexplicable economic mystery: the tale of the many service stations.

While modern-day Crestline might seem like a mecca for someone in need of a place to cash a check, with its seven banks and all, the opposite was true of the area in the mid-1900s. There was a Gulf station, a Pure, a Sinclair, a Standard, a Shell and others—at one point there were at least seven places to get gas in the tiny village.

Fred Renneker, who grew up off Pine Crest Road, remembers this fact with an intensity that can only be aided by poetry. Fred’s father made up a little rhyme for the surplus: “Hush little vacant lot, don’t you cry. You’ll be a filling station by and by.” What the community needed with so many gas stations is anyone’s guess.

Crash Landing

Crash Landing

Henry Mellen, 72, still lives in the same house he grew up in on Country Club Road. Like many of Crestline’s older residents, he never really considered living anywhere else. Aside from memories of smaller, younger Crestline, Henry also holds claim to one of the more outrageous stories of a deathless plane crash captured in an early photograph near his home.

“It was on a Thursday,” he explains. “[My friend John] and I were walking back from grade school and we saw this plane, and it sounded like the engine was cutting out. We looked up, and even at that age we could see that plane looked like it might be in trouble…We didn’t see it hit the ground, but we saw it heading towards the ground. So, we took off running.” The small, propeller-engine craft had headed for a crash landing over the Birmingham Country Club, arching downwards.

“When we got there the plane was upside down on its back, and if there was anybody hurt it wasn’t bad. Nobody was killed,” Henry says. In the meantime, a small crowd of onlookers young and old gathered around to make sure everyone got out safely.

Editor’s Note: Writer Rick Lewis used the following resources for research for this article in addition to interviews with the people he quoted: Images of America: Mountain Brook by Catherine Pittman Smith, A History of Mountain Brook Alabama & Incidentally of Shades Valley by Marilyn Davis Barefield and Crestline: A Timeless Neighborhood by Helen Pitman Snell. If you or a family member have stories of historic Crestline to share, we are considering writing a Part II of this article; email mm@mountainbrookmagazine.com for more information.