Marching through the tall grass, a soldier prepares to fire against the Confederacy, his palms sweating as he awaits what could be the final battle of the American Civil War. He’s not just a stranger in a history book either. You know his name, his regiment, how old he was and where he fought. And you know he’s your relative, all thanks to a family ancestry project for your tenth-grade U.S. History class.

Through this project, Jake Collins’ students have uncovered countless tales from their families, connecting history with personal stories. “I have had a student who descended from slaves sitting next to someone who comes from a family who owned hundreds of slaves,” he says. “It was really important for others in the class to watch those two students have a conversation about slavery and its impact on our country today. I have also had students sitting next to each other who had ancestors that literally fought against each other at places like Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga.” This year, Collins even discovered that one of his students was actually his distant cousin through a Civil War veteran.

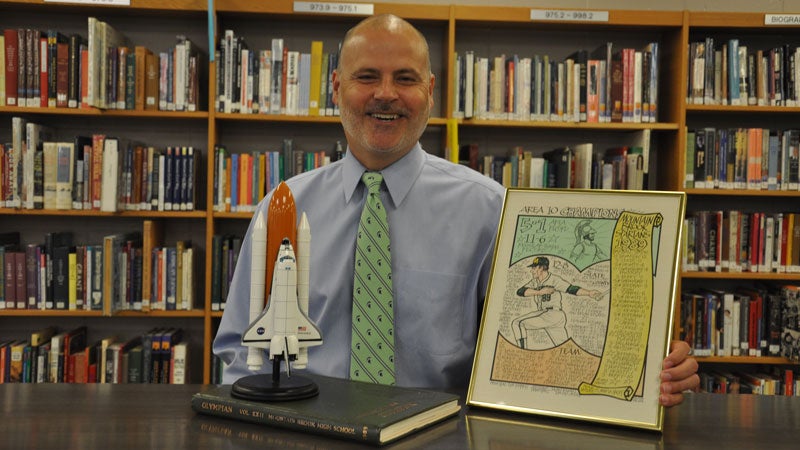

Collins, an amateur historian and author of Images of America: Homewood, has always looked for creative ways to help students connect to history. Prior to coming to Mountain Brook, Collins taught at Homewood Middle School for three years. There he created a social media project through Instagram for his students called the “Homewood History Hunt” to instill a love and appreciation for the history of Homewood. When he came to Mountain Brook High School in the fall of 2015 to teach, he knew exactly how to help students connect to United States history. Collins has always dabbled in genealogy and knew there was a grant available for high schools. All students at MBHS have free access to ancestryclassroom.com to discover ancestors, fold3.com to research military records, and newspapers.com that provides access to hundreds of papers throughout the country, and in his class, they put those resources to good use.

Collins, an amateur historian and author of Images of America: Homewood, has always looked for creative ways to help students connect to history. Prior to coming to Mountain Brook, Collins taught at Homewood Middle School for three years. There he created a social media project through Instagram for his students called the “Homewood History Hunt” to instill a love and appreciation for the history of Homewood. When he came to Mountain Brook High School in the fall of 2015 to teach, he knew exactly how to help students connect to United States history. Collins has always dabbled in genealogy and knew there was a grant available for high schools. All students at MBHS have free access to ancestryclassroom.com to discover ancestors, fold3.com to research military records, and newspapers.com that provides access to hundreds of papers throughout the country, and in his class, they put those resources to good use.

The assignment begins in the fall when Collins sends home a family tree packet at Thanksgiving break and instructs students to get their grandparents, aunts, uncles and anyone else interested to help them fill out as much information as possible. At the end of the third nine weeks, the assignment becomes more clear: Trace your family tree back to at least the time of the Civil War, and then create either a poster focusing on an ancestor’s military records or immigration/migration records, or a paper defending a Civil War veteran. Students also have the option to create their own assignment. Ultimately, the project tends to dig not just into history but all the more so into family ties, often into finding a particular ancestor of interest.

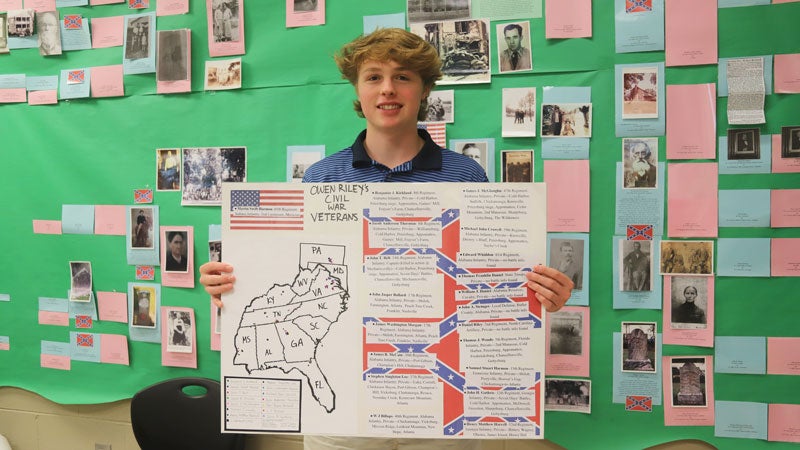

For senior Owen Riley, “The project helped me to cultivate my personal identity.” He learned of new aspects about his family’s past in the Confederacy and even found out that he is a distant relative with another student due to a common ancestor. His project focused on the battle plans and military records of his ancestors, including soldiers from the battles of Shiloh, Vicksburg, Gettysburg and Appomattox. “It made the unit much more interesting because I made a personal connection with it through what I was learning from my research,” he says.

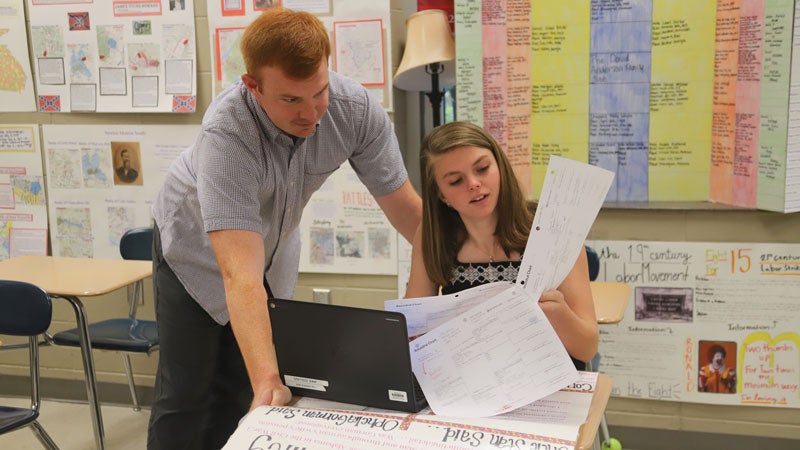

Jake Collins with Kate Dyleski

2018 graduate Kate Dyleski learned the importance of credibility when she discovered information that differed from history as her family knew it. She had grown up hearing from her uncle that her great-great-great-grandfather, James Madison Gorman, was captured during the Civil War in Salem Church during the Battle of Fredericksburg. So when she also found through research that her great-great-great-grandmother, Ophelia Gorman, filed a pension claiming her husband was never captured, Kate was conflicted with who to trust for the most credible information: a trustworthy and knowledgeable secondary source who she knows well, or a first-person and directly associated primary source who she has never met.

She ended up focusing on source reliability for the second half of her project and was surprised by how much it affected her family. “This isn’t just a project parents ignore or don’t care about,” she says. “For me, it was a project my whole family was excited for because everyone was so interested in the final product and finding the truth.”

Collins has also seen siblings complete the project in different ways, expanding family trees or taking the project in opposite directions. When he had 2018 graduate Ford Clegg during his first year of teaching at MBHS, Ford set the example for future students completing the project. So his younger sister junior Anne Carlton Clegg had to get creative when the time came around for the project to begin. She ended up getting to see her family’s impact across Alabama as she found properties they owned in Bullock County, Randolph County and Clay County. She also found reports of slave owners within her family, which helped her put certain aspects of her life into perspective.

Ford and Anne Carlton Clegg

Like many of his classmates, junior Charles Regan’s research led him to create his own project. At the outset, he had uncovered Civil War era drawings by his German ancestor, Charles Ludwig Meister. As it turns out, Meister was an architect before the American Civil War and later became a typographer for the Confederate Army.

Speaking of German ancestors, junior Michael Schmidt learned his ancestor Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler was one of the first pioneers of the internal combustion engine, helping to create the first Mercedes-Benz car in the late 1800s and the world’s first motorcycle in 1885. “I had no idea, and I was excited to learn more about him from my relatives,” he says.

After all, the heart of the project is not just learning history. It’s about digging into a next-level layer of family. As Michael says, “The project has definitely helped me get to know my family better and discover certain traits I may have inherited from my great-great-grandfather, which is something I probably would not have taken the time to discover without being assigned this project.”