Black and white photographs, newspaper clippings, theater brochures and song books cover Harriet Cochrane’s dining room table at her house in Cherokee Bend. “I haven’t even been able to go through all of it myself,” she says. Fortunately, she had a guide. Her grandfather Richard M. Kennedy wrote an autobiography so his family would have a record of his life as a theater magnate in the golden age of Hollywood who hosted stars and industry pioneers from Clark Gable to Bob Hope at his home on Overhill Road.

Kennedy’s unpublished autobiography traces the history of the theater and movie industry, including the shift from silent movies to “talkies,” union conflicts, and competition with radio and TV. He describes local events, such as the construction of the Alabama Theatre in 1927 and Birmingham population shifts towards the suburbs, against the backdrop of the Great Depression, World War II and the Civil Rights movement. To Kennedy, movie theater management was not just a business, but an art that allowed him to support his family and serve his country. More than just a businessman, Kennedy was a patriot, a devoted family man and a showman.

Moving to the Magic City

Kennedy was born near Montgomery in 1902. After his father died in 1920, he knew he would have to work instead of attend college. Robert B. Wilby, the owner of several theaters in Montgomery and Selma, had recently acquired the Strand and Colonial Theatres in Birmingham. He offered Kennedy $25 per week if he would move to Birmingham to help manage his theatres.

On June 5, 1920, just a few weeks after graduating from Lanier High School, Kennedy took the L&N train to Birmingham for the first time. “Leaving home and all that was near and dear to me was a traumatic experience and more than I thought I could bear,” he wrote, “but even this was better than ‘selling pencils all the rest of my life,’ the way I felt about it at the Mercantile Paper Company,” where he had turned down a full-time job offer that would have allowed him to stay with his mother.

Life in the city was a difficult adjustment. “Birmingham, to me, at that time, was the coldest, most impersonal spot on the globe,” he wrote. With only a few connections and a meagre salary, he would have to find a new community in a strange new place at age 18. Kennedy dove into his work, gaining experience from the manager’s office to the projection booth.

Photo by Laine White

The Golden Age of Hollywood

The late 1920s were a period of immense change and growth in the movie industry. In 1929, The Jazz Singer featuring Al Jolson premiered at the Strand as the first “talkie” shown in Birmingham. Paramount-Publix opened the Alabama Theatre the day after Christmas in 1927. Kennedy watched the construction of the Alabama Theatre with great interest. “One of my greatest ambitions had been to someday have a chance of operating the Alabama,” he wrote, “but I never dreamed, at that time, that the opportunity was going to be mine.” But it was. In 1932, he became the manager for the Alabama Theatre. Under his leadership, the theater started the Mickey Mouse Club in 1933 and began hosting the Miss Birmingham and Miss Alabama pageants in 1935.

Kennedy’s first wife, Marie Wheeler, passed away after childbirth in July 1934. Wilby suggested he take a month off, and close friends recommended putting his two children in a children’s home. In spite of his devastation, Kennedy was determined to carry on as usual. Christmas that year “reopened old wounds,” Kennedy wrote, but he was looking forward to a trip to Los Angeles to see Alabama play in the Rose Bowl—a gift from his district theater managers.

The train to Los Angeles took four days. The night after Kennedy’s arrival, movie star Dick Powell invited him to dinner at the Beverly Wilshire hotel with a “small crowd” that included Oscar Morgan, Regis Toomey, and Toomey’s date, an Olympic swimming star who had gone into the movie business (“the name escapes me,” Kennedy wrote). Powell had asked actress Joan Marsh to be Kennedy’s date for the evening.

Kennedy reported Hollywood gossip with a Southern man’s raised eyebrow. At the end of the evening, Regis accepted an invitation for himself and his wife to attend the Rose Bowl with Kennedy. “I thought it very strange that Regis, a married man, would have a date with a beautiful starlet one night and then take his wife to a football game the next day, but that was the way actors behaved in those glamorous days at Hollywood,” Kennedy commented.

The night before the game, Kennedy met Bing Crosby at Paramount Studios. Crosby was betting ping pong tables that Alabama would lose. “I don’t know how many bets he had,” Kennedy wrote, “but I am sure that he lost at least a half-dozen Ping Pong sets.”

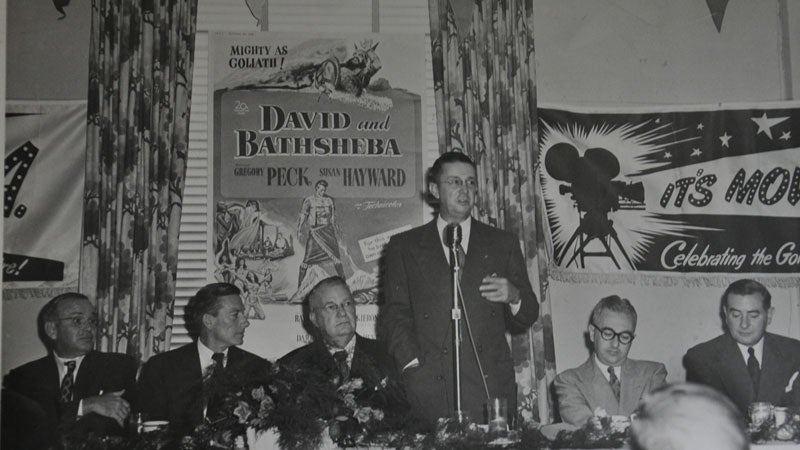

Richard Kennedy, right, with Susan Haywood, who won the 1958 Oscar for Best Actress in I Want to Live.

The Theater on the Home Front

The life of a movie theater manager in the first half of the 20th century was about much more than parties with movie stars though. During World War II, Kennedy led theater managers across the country in promoting home front support for war efforts. Both Paramount Pictures and 20th Century Fox pledged to sell war bonds by offering purchasers exclusive seating and by showing newsreels and films on rationing, enlistment and espionage. Kennedy considered his involvement in the War Activities Committee as his greatest contribution to his country.

Special shows, often with movie stars in attendance, were incentives for citizens to buy war bonds. At one New York show for which Kennedy was partially responsible, the stars included Lana Turner, Kathryn Grayson, and Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra. Whiteman had asked Betty Grable to join him onstage, but the show management worried that Turner would be upset at the idea of sharing the headline. As compensation, they left extra bottles of whiskey in Turner’s dressing room, and Kennedy assured her that Grable would not sing and dance.

Backstage before the performance, however, Kennedy found Grable in tap shoes ready to sing and dance. Knowing it was too late, Kennedy went to his seat. After Grable’s show-stopping performance, Turner came onstage in a white gown “shaking like a leaf.” Kennedy wrote that she admitted to the audience that she had a report on war bond sales but was too nervous to read it. The audience loved it. Although the event was a success in spite of the unexpected turn of events, Kennedy was afraid to go backstage after the show.

Kennedy’s involvement in war bond sales as well as with the March of Dimes earned him an invitation to the White House on December 19, 1944. As a Southern conservative, he was never a fan of President Franklin Roosevelt, although he admitted that he enjoyed their meeting. The next year, Kennedy attended another White House reception, this time with President Truman. Kennedy did not admire his “socialistic policies,” but he found Truman to be a “very courageous man.”

During World War II, Kennedy traveled to cities across the country promoting the movie industry’s involvement in selling war bonds to support war efforts.

Life and Legacy

In spite of his frequent travels and his relationships with movie stars and politicians, Kennedy enjoyed living in Mountain Brook with his family. Richard and his second wife Harriet (“Mimi”)Stallworth frequently invited friends and family to singalongs at their house on Overhill Road in the 1960s. The Birmingham Post even included a brief note on the gatherings: “Well, I’ll have you know this dandy group above can really sing…and if you don’t believe me ask any—and I do mean ANY one on Overhill Road!”

Carter Kennedy—Harriet’s father—recalls meeting some of Kennedy’s famous friends as a child on Overhill Road. Bob Hope was a frequent visitor, and their family watched pre-released movies on 16 millimeter film and sampled pre-release concessions like Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups with friends. Carter was also a member of the Birmingham Mickey Mouse Club when it was the largest of its kind.

“[My father] wasn’t a pessimist, but he always faced a lot of challenges,” Carter said. At various times, Kennedy worried that radio or television would put him out of business. Even daylight savings time, which meant that summer drive-in movies could not start before 8:30 p.m., posed a threat. Still, Kennedy adapted, whether by pushing his theaters to place more emphasis on concessions or by broadening the scope of theater programming.

Kennedy passed away from heart failure in 1979 at age 77. His legacy, however, lives on in the treasure trove of historical documents he left with his family as well as in the revitalization of historic Birmingham venues such as the Alabama and Lyric theaters.

While writing his autobiography in the mid-1970s, Kennedy frequently commented on how lucky he felt to have lived such an extraordinary life. “They say that all an old man has is his memories,” he wrote. “Like the click of a camera, I can jump to Rio de Janiero and be gliding past Sugar Loaf on the Nieuw Amsterdam or hop in a second all the way to Paris where we are enjoying an aperitif at the Café de la Pax. I can project back to Honolulu and see again Bill Britt presenting us with decorative leis as we sailed on the Matsonia or jump down to Buenos Aires and be the guests of the Pardos in their lovely and picturesque home.”

More than just a businessman, Kennedy was a showman. The impersonal, unrefined experience of the modern movie theater would disappointment him. A movie, he believed, should be an escape from everyday life. Furthermore, the theater should serve its community by providing an enjoyable experience as well as by supporting patriotic causes. “I know full well that as a theatre manager today, I would be a flop, for I could not provide the type of entertainment the young people of this generation want,” he wrote in 1975. “I am content, however, with the knowledge that I have been a satisfactory showman. And between you and I, I still am.”

Richard Kennedy Through the Years

1902: Richard Kennedy is born in Montgomery.

1927: Kennedy and business partner/mentor Robert Wilby own the Rialto and three theaters in Ensley.

1934: A fire takes hold in downtown Birmingham, but the Alabama Theatre is spared.

1935: The Alabama Theatre begins hosting the Miss Birmingham and Miss Alabama pageants.

1937: Kennedy purchases and renovates his home at 3108 Overhill Road.

1938: Kennedy marries Harriet Stallworth (“Mimi”), celebrating with a barn dance at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel. They spend their honeymoon in Europe on the eve of World War II.

1942: Ed Leigh McMillan of the US Treasury asks Kennedy to lead the war bonds efforts with the motion picture industry in Alabama.

1944: Kennedy becomes president of the Birmingham Rotary Club and visits President Roosevelt at the White House.

1945: Kennedy attends a reception with President Truman at the White House.

1949: The Supreme Court breaks up the Paramount monopoly on producing and distributing movies.

1961: Kennedy meets with Bobby Kennedy at the White House to discuss how to desegregate movie theaters.

1979: Kennedy dies at age 77.